Russian Hopes of Sanctions Relief Fade Amid Ukraine Deadlock

When it comes to sanctions relief for Russia, the last step might be the most difficult.

After the U.S. and Europe dangled the prospect of an easing of sanctions for the first time last month, the political deadlock in Ukraine and renewed tensions over Syria are dousing expectations of a breakthrough.

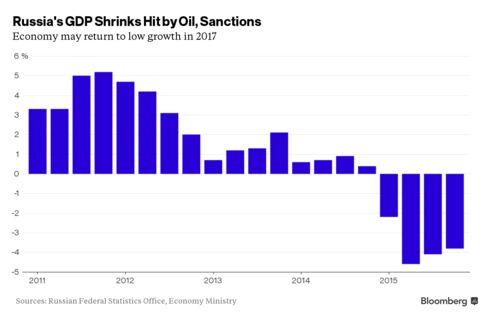

The timing couldn’t be worse for Russia, which is mired in its longest recession in at least two decades amid a collapse in oil prices to a 13-year low. Obstructing the way is a failure by both sides to implement their obligations under a peace deal signed in the Belarusian capital of Minsk a year ago.

“The grim economic realities make a reset of relations with the West a dire necessity for Russia,” said Lilit Gevorgyan, senior economist at IHS Global Insight in London. While there’s “certainly a momentum” to push through the Minsk deal “as Russia is showing more flexibility, forced by the worrying economic outlook,” the “chances of a successful settlement of the conflict are not looking good, because a great deal of cooperation is required not only from Russia but also Ukraine.”

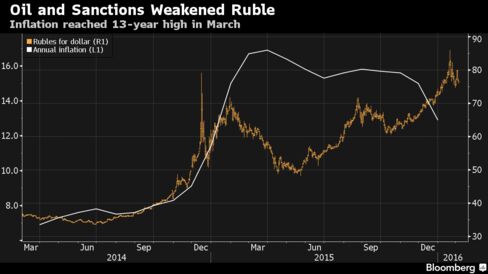

More than 9,000 people have died and several million fled their homes during nearly two years of fighting in eastern Ukraine that sparked the worst crisis between Russia and its former Cold War adversaries since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The European Union will review its sanctions in June, while the U.S. measures remain in place until repealed. The sanctions and plunging crude prices have pushed Russia toward a second year of recession, its worst contraction of the Putin era, with the ruble hitting record lows against the dollar and a ballooning budget deficit.

Shaky Truce

The Ukraine cease-fire remains shaky a year after the peace deal. International monitors last week warned of an increase in violence, while the insurgents are keeping observers out of border areas where Ukraine suspects heavy weapons and Russian troops remain. Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, beset by economic troubles and divisions within his government, seems unable to deliver on a pledge to offer more autonomy to pro-Russian secessionists.

Hopes of greater cooperation between Russia and the West are also foundering after the collapse of Syrian peace talks last week as Europe faces an upsurge in refugees fleeing a Russian-backed offensive. German Chancellor Angela Merkel said Monday she’s “not just shocked but outraged” by the human suffering caused by the offensive, including Russian airstrikes.

There isn’t “any credible evidence” to support Merkel’s criticisms of Russia’s air campaign, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told reporters on a conference call Tuesday. “We didn’t hear similar assessments two or three years ago about the barbaric actions of terrorists” in Syria, he said.

Munich Meetings

Russia is “engaged in two military operations, one in Ukraine and one in Syria” and it “wants some kind of resolution of both these crises,” William Pomeranz, deputy director of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, said in a Bloomberg radio interview Monday. This comes as the plunge in oil prices is having “a devastating impact on a variety of different countries, most notably Russia.”

The U.S. and European states will seek to move the Ukraine peace process forward on the sidelines of this weekend’s annual Munich Security Conference, which Poroshenko and Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev are due to attend. Merkel, who together with French President Francois Hollande helped to negotiate the peace deal, was downbeat about the prospects for progress last week.

Poroshenko can’t muster the two-thirds majority in parliament for constitutional changes granting more powers to the separatists, with three of four parties in the ruling coalition opposed, a senior presidential official in Kyiv said. The government suffered a new setback last week when Aivaras Abromavicius, its reform-minded economy minister, quit, complaining that his efforts to fight corruption were being sabotaged.

Troops, Talks

Russian officials say privately that they don’t expect any breakthrough. A senior European diplomat in Moscow said there’s skepticism about progress without a major compromise even though the Russians have begun to show they really want financial sanctions lifted.

Russia, which has opposed Ukraine’s efforts to move toward joining the EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, has denied U.S. and European accusations that it backed the insurgents with troops and weapons, though President Vladimir Putin said in December that some Russian military were in the neighboring country.

The Kremlin raised hopes that it wants the peace accord enforced by naming a political heavyweight with access to Putin, former parliament Speaker Boris Gryzlov, as its new envoy in December to a contact group charged with implementing the deal. Gryzlov went to Kyiv to meet Poroshenko last month and that was followed by a series of meetings between the U.S., Russia, France, Germany and Ukraine to try to break the logjam. Still, the latest peace talks in late January failed to deliver progress, with the government in Kyiv blaming Russia for delays in the accord’s implementation.

With major companies cut off from international financing and restrictions on its energy industry, Russia is “pretty desperate” to get the sanctions lifted, said Tim Ash, head of EMEA credit strategy at Nomura International Plc in London. The economy in 2016 will contract for a second year, by 0.7 percent, according to analysts polled by Bloomberg.

Even so, the stalemate is hard to overcome, said Joerg Forbrig, senior program director at the German Marshall Fund of the U.S. in Berlin. “Russia still wants to get a Ukraine resolution on its terms,” Forbrig said. “But the Ukrainians are quite stubborn.”

Open all references in tabs: [1 – 5]